SCARCE Explores Slovakia's Mining Heritage

11.04.2025

Author: Claire Sabel

10min read

Research Report

Introduction

Some 20,000 objects stretching 7km make up the collections of the Slovakian Mining Archive (Slovenský banský archív) in Banská Štiavnica, Central Slovakia, a beautifully preserved historical mining town nestled in the Inner Western Carpathian mountains. This mountain of paperwork documents the excavation and management of the Banská Štiavnica-Hodruša mining complex, developed over the better part of the last millennium, and whose approximately 100km of underground tunnels run directly beneath the town and its environs. The surface-level veins of the region’s rich metal ores (formed in the caldera of a long-extinct supervolcano) were already exhausted by the twelfth century, requiring mining operations to venture underground. Aided by German-speaking investment, technology, labor and expertise first solicited by the region’s Hungarian rulers in the thirteenth century, Banská Štiavnica evolved into Europe’s oldest, oldest continually operating, and most productive mining regions, and also one of its best documented. The region’s technical mining structures were recognized with UNESCO World Heritage Status in 1993, and the archival maps and plans covering mining from the seventeenth to twentieth centuries were inducted into UNESCO’s Memory of the World Register in 2007.

The SCARCE team visited Banská Štiavnica in February, 2025 to study the textual and architectural history and heritage of this mining region. Over the course of five days, we explored mines on foot and across hundreds of pages of mining manuscripts, under the expert guidance of Dr. Peter Konečný, who heads the Slovenský banský archív and is a key partner of our project.

Outside the Slovakian Mining Archive

SCARCE Team at work

The History of the Slovakian Mining Archive, Banská Štiavnica, and Schemnitz

The archive in its current iteration was founded in 1950 as part of then-Czechoslovakian National Archives and has been an independent part of the Slovakian national archives since 2015. The collections were originally the working administrative records of the Habsburg mining administration which began operating the mines in the sixteenth century. The extensive mining records were analyzed, revised, revisited and re-ordered throughout their long lifespan of use in managing the “Hungarian” mining towns of what is now Central Slovakia.

Even during the Communist era (when Czechoslovakia was a satellite state of the Soviet Union), Habsburg-era mining records were used to help guide further mineral prospecting: the documents from the Communist period which now form part of the historical collections include considerable historical context about their Habsburg pasts. After the end of Communist rule in Slovakia in 1989, and the separation of Slovakia from Czechia (then the Czech Republic) archival collections relating mining from the rest of Slovakia were brought to Banská Štiavnica’s mining archive. The archives themselves have long been a resource to be sustained and managed.

Central Slovakia Museum, Banská Bystrica

It took the better part of the week to grasp the complex administrative history of these archives. During the early modern period, Schemnitz was one of several Central European mining areas controlled by burghers of German descent, who had arrived during the so-called “Ostsiedlung” of the thirteenth century and become the leading mining investors and property owners of free mining towns (Bergstädte). After the Habsburg double wedding of 1515, a number of Hungarian and Bohemian mining towns, including Schemnitz, were given to Queen Maria of Habsburg (subsequently known as Maria of Hungary) as part of her dowry, following a Hungarian tradition established in 1424. Following the death of her husband Lajos II of Hungary, during the 1526 Battle of Mohacs against the Ottomans, the kingdom of Hungary was divided between Ottoman and Habsburg rule, and Mary’s brother Ferdinand I (who would be crowned Holy Roman Emperor in 1556) became King of the northern part of Hungary (Lower Hungary), which included what is now Slovakia and its mining towns in 1548. It took some decades for the Habsburgs to gain control over the Hungarian mining administration. Ferdinand attempted to reform the administration throughout his rule but faced resistance from the Hungarian Diet and the towns themselves who had traditionally controlled their own mining privileges. Ferdinand’s successor Maximilian resumed the negotiations, and “Maximilian” mining laws were finally accepted in Schemnitz in the 1570s.

The effects of these reforms were to subjugate the mining administration in Schemnitz to control from Vienna, and the flow of reporting and decision-making between Vienna and Schemnitz structures much of the archive. In turn, Schemnitz, as the most economically significant mining town in Lower Hungary, maintained administrative authority over other towns, the most important of which were Neusohl and Kremnitz. An important mining academy was created in Schemnitz in 1735, which was reformed and enlarged by order of Maria Theresa in the 1762, nearly contemporary to the Bergakademie at Freiburg in Saxony. As with the rest of the Hungarian mining administration, the Bergakademie switched from Austrian (and hence German speaking) administration to Hungarian administration in the second half of the nineteenth century. In 1919 the academy was relocated to the newly created Hungarian nation after the creation of Czechoslovakia after the first World War. The evolution of the archive was definitively structured by these waves of political reorganization, resulting in a range of printed and manuscript finding aids in German, Hungarian, and Slovakian.

Historical Mines and Mining History in Central Slovakia

In addition to mornings spent analyzing sources and secondary literature in the archives, the SCARCE team also visited several important historical sites in and around Banská Štiavnica. We had the opportunity to compare different approaches to contextualizing and communicating early modern mining history through the perspective of a preserved town and its archives in Banská Štiavnica, to a regional municipal museum in Banská Bystrica (Neusohl), and the private museum and tour led by an active mining company in Hodruša.

In Banská Štiavnica, there are an abundance of well-preserved buildings from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, many of which are connected to existing mining shafts and adits. There is also a wealth of interpretive material distributed around the outskirts of the town, much of which is integrated into well-signed hiking routes. Our delightful hotel was just around the corner from the Kammerhof, the administrative seat of the mining administration, which now houses a key part of Banská Štiavnica’s mining history museum.

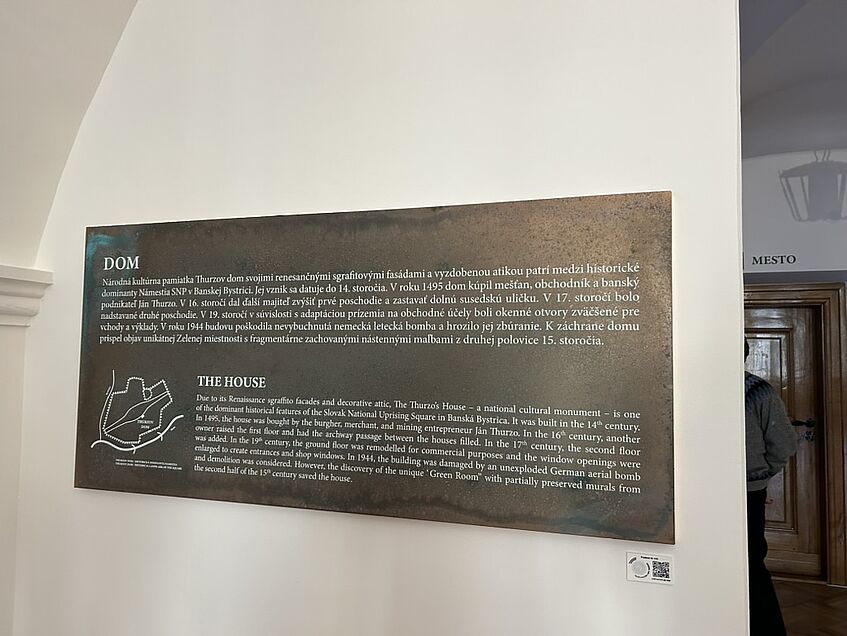

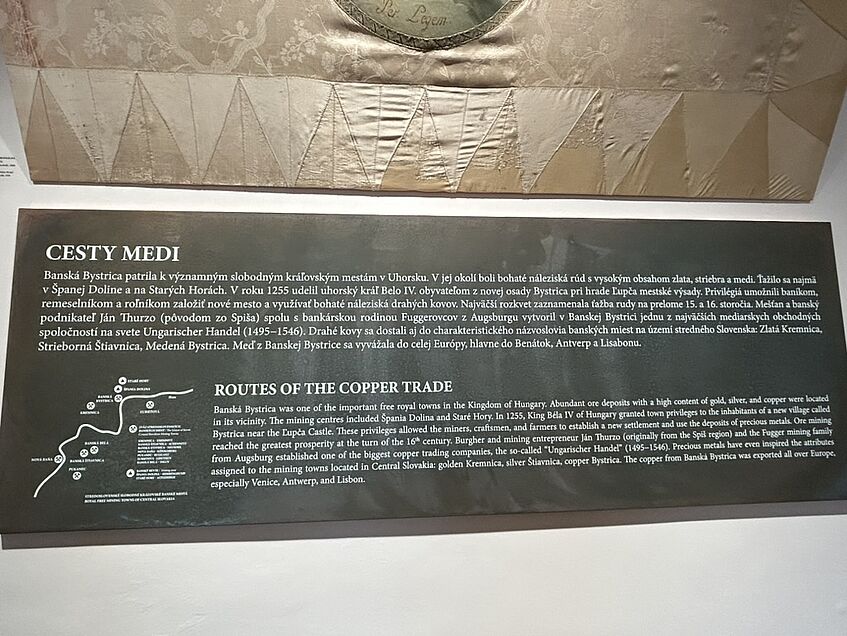

In Banská Bystrica (Neusohl), we visited the Central Slovakia Museum, a museum of Central Slovakian history and culture, located in the house that belonged to mining entrepreneur and engineer Jan Thurzo since at least 1495. Thurzo partnered with Jakob Fugger to develop an extremely profitable monopoly over the copper trade in the Holy Roman Empire in the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries. The museum used the copper trade as a motif linking together the region’s different historical eras, materialized in interpretive signs printed on copper plates:

Signs printed on copper highlighting the region’s historic connections to copper mining

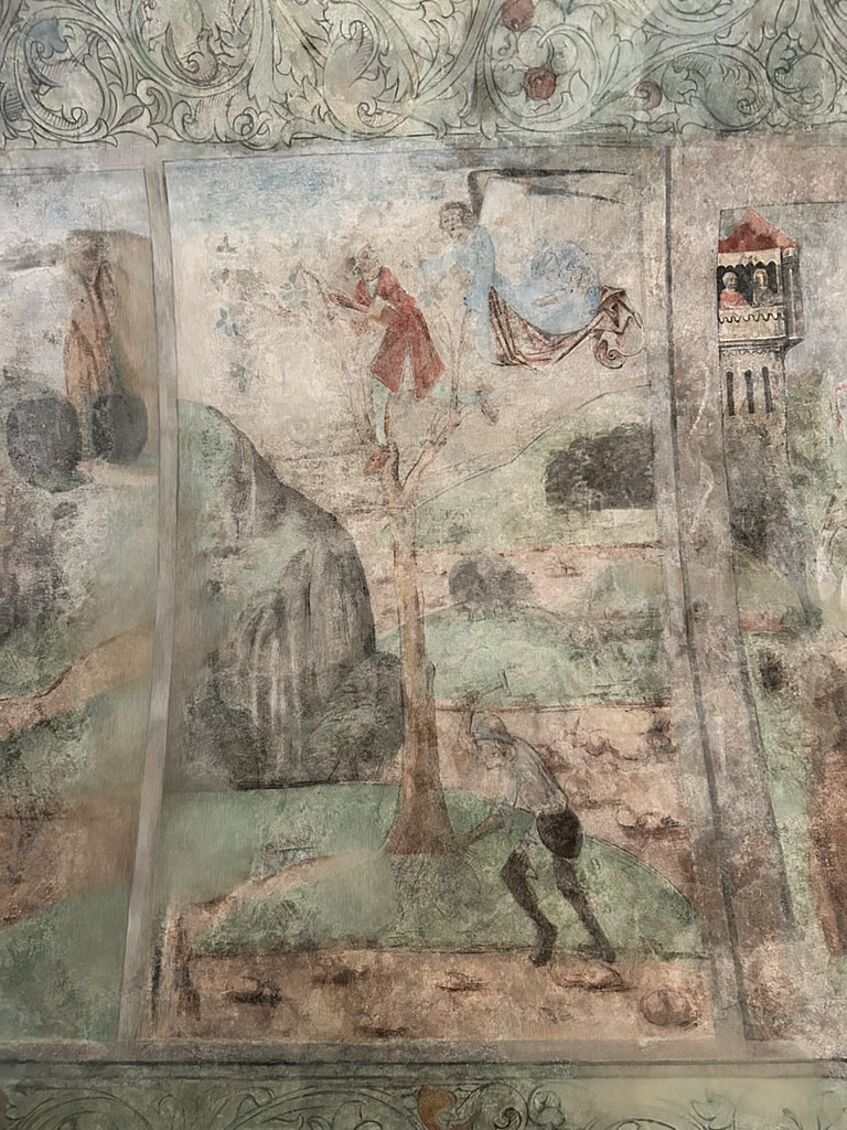

Daniel’s dream and a miner’s discovery, in the Green Room at the Thurzo house

Mineral resources were also a theme in the pictorial program of the museum’s “Green Room” dating from the late fifteenth century, which made extensive use of malachite for its pigment, a copper carbonate mineral that is found naturally sedimented in a water source near Banská Bystrica. Several other contemporary “green rooms” have survived in other elite residences from this period. The wall paintings included a number of saints with significance to miners, including St. George, St. Christopher (protector against sudden death) and the prophet Daniel, whose dreams and visions were linked to visionary discovery of precious minerals.

We also noted in interpretative materials across different sites that there were various terms used to describe the origins of German mining communities in Slovakia, ranging from “guest” to “colonists.” One guide book even referred to German miners as “guest colonists”! This ambiguity reflects the complex history of migration and shifting sovereignties in the region, refracted through the complex and fractious histories of twentieth century nationalisms.

In addition to interpretive differences, the mining landscape was itself diverse. In Neusohl, the houses of burghers and the market function of the town were significantly more removed from the actual mines and deposits than in Schemnitz, where miners lived in and among the mountains they mined and could descend underground from the very center of town. The contrasting topographies of the two sites was also a significant factor in subsequent growth and preservation. The steep slopes of Banská Štiavnica were much more restrictive of buildings and roads (not to mention the underlying network of tunnels), whereas Banská Bystrica was much more flat. Banská Štiavnica’s medieval core was as a result extremely well preserved.

Exmaining minerals from Rozália mine

Entering Rozália mine

Example of a mine shaft excavated by hand! Up until the end of the seventeenth century, two men could extend a tunnel by 10-20m per year using metal tools, before the introduction of explosives.

Lastly, in Hodruša we visited a part of the historic Rozália mine, which had been operated from the Middle Ages until 1950, only to be reopened in the early 1990s as a private mining company, which operates in an extension of the historic mine. The company purchased and renovated several historic buildings, and preserves its own collection of historical materials, including hand drawn maps, which they continue to use and update in conjunction with 3D models. Our guide emphasized the historical continuity between traditional handwork and artisanal skills and modern industrial technology. He described the work of three geologists and three surveyors employed by the company who entered the mines daily to determine where to exploit next, and the ironsmith who still works with the firm to sharpen and maintain metal tools.

In spite of our best efforts to sustain our own mental and physical resources with ample helpings of bryndzové pirohy (Slovakian cheese dumplings), the SCARCE team was thoroughly exhausted after a week of prospecting and assaying different sites of mining history. We look forward to sharing future updates on the blog as team members disperse to pursue their own veins of research in the coming months!

Further Reading

Tibor Turčan, Peter Zámora, and Jozef Vozár, eds., History of Mining in Slovakia. Utilization of Minerals, Ore Extraction, Some Selected Non-Metallic Minerals and Metals Production on the Territory of Slovakia since Ancient Time till 1990 (Košice: Banska agentura, 2008)

Rainer Slotta and Jozef Labuda, eds., “Bei diesem Schein kehrt Segen ein”: Gold, Silber und Kupfer aus dem slowakischen Erzgebirge (Bochum: Deutsches Bergbau-Museum, 1997)

Jozef Vozár, Das Goldene Bergbuch: Schemnitz, Kremnitz, Neusohl (Bratislava: Veda, 1983).

Peter Konečný, “Sites of Chemistry in the Schemnitz Mining Academy and the Eighteenth-Century Habsburg Mining Administration,” Ambix 60, no. 2 (2013): 160–78